Yesterday's Men: The decline of two English Giants

On DECEMBER 13, 2010, Manchester United welcomed Arsenal to Old Trafford. It was a dire game won by a lucky header from United’s Park Ji Sung. It also featured a comically miscued penalty from Wayne Rooney, a rare start for Marouane Chamakh and even a fully fit Jack Wilshere.

Arsenal began that chilly evening in first place. United in second. At the time, this was hardly remarkable. The pair had shared 12 of the previous 15 titles, and locked out the top two places in five of those years. Only two teams - Chelsea and Liverpool -had managed to break their stranglehold on the Premier League trophy.

Yet ten years on, that fixture remains the last time that Manchester United and Arsenal contested a top-of-the-table showdown.

And as both sides sink ever deeper into a self-reflective quagmire, it is reasonable to ask when and if they will ever do so again. Overdramatic? Perhaps. But when Everton and Liverpool were carving up honours in the 80s, few imagined the Merseyside hegemony would dwindle so fabulously.

It is now been 30 years since either team won the First Division, let alone fought each other for supremacy. Who today can honestly envision a return to those untroubled days?

United and Arsenal are yesterday's men. And the truth is, they lost touch long before that meeting at Old Trafford.

Initially, the arrival of Roman Abramovich at Chelsea and, later, Sheikh Mansour at Manchester City robbed both of their position at the top of the food chain. Yet, just like a good driver can drag a dreadful F1 car up the grid, teams unable to compete financially were kept competitive by skillful and experienced managers. Sir Alex Ferguson's final title in 2013 ranks just behind Leicester City in terms of Premier League miracles, as the regular presence of Tom Cleverley in the starting XI attests.

At the Emirates, Arsene Wenger's ability to hold on to top-four finishes out of successive mediocre teams can only now be fully appreciated. Eventually, though, even that proved beyond the Frenchman, just it would have for Fergie had he not felt the winds of change and craftily departed with his legacy intact.

Because whilst United and Arsenal backed their managers to deliver success - a strategy rooted in the previous century - rivals were looking to the future. Some (Liverpool, Spurs, Leicester) invested in sporting directors and other technical staff to hatch coherent long-term recruitment plans. Others, most notably Chelsea, spent heavily on youth development.

In both cases, the aim was manifold: to construct a conveyor-belt of talent; to mitigate against managerial change, to identify value where others did not. And, later, to ensure compliance with Short Term Cost Control (STCC).

STCC is the Premier League's version of Financial Fair Play. Since 2016, sides in the top division have had to show that salaries do not rise by more than £7 million per annum, though this limit rises in line with any extra income generated. “Extra” meaning- player sales, sponsorships and prize money for consistent Champions League qualifications. Upon those three rocks, United and Arsenal have suffered disaster. United have still managed to earn their keep with jersey sales and long-term sponsorship deals. The same can’t be said for Arsenal, though.

Because there was no real transfer strategy beyond listening to the gaffer, both clubs performed badly in the transfer windows. Leicester, for instance, bought Harry Maguire from Hull City in 2017 for an initial fee of £12m.

Last summer, the central defender was sold to Manchester United for £80m, a profit of some £68m.

Now consider a report from the dailycannon.com that in January explained how Arsenal have brought in a total of just £77 million for- deep breath- Jogan Djourou, Denilson, Andrei Arshavin, Andre Santos, Marouane Chamakh, Sebastian Squillaci, Gervinho, Nicklas Bendtner, Lukas Fabianski, Bacary Sagna, Lukas Podolski, Serge Gnarby, Tomas Rosicky, Abou Diaby, Kieran Gibbs, Gabriel Paulista, Wojciech Szczesny, Francis Coquelin, Olivier Giroud, Santi Carzola, Jack Wilschere, Lucas Perez, Joel Campbell, Mathieu Debuchy and Jeff Reine-Adelaide. And that’s not profit, by the way, THAT is fees.

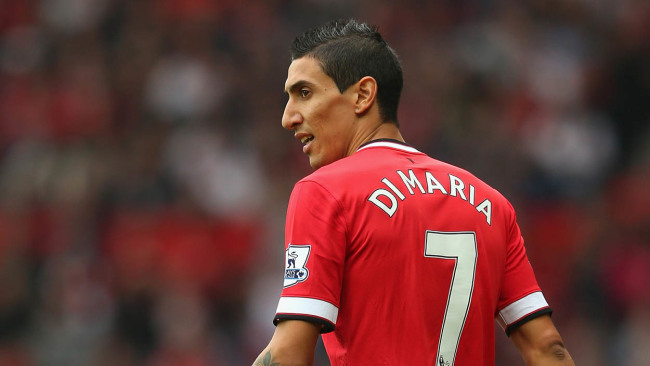

United’s balance sheet is littered with similar markdowns. Like Angel Di Maria, who was signed for £59m and sold for £44m. Or Henrikh Mikhitaryan, signed for £38m and swapped for Alexis Sanchez, who is now on load at Inter Milan after scoring three times at a cost of £11m per goal. And don’t forget Marouane Fellaini, who was bought for £27.5m (at a time when Chelsea’s highest ever transfer fee was lower), four million more than the buyout clause that United had allowed to expire just six weeks earlier.

That is what happens when your transfer policy is dictated by a succession of idiosyncratic decisions by a businessman (and not a very good one as the numbers suggests) who doesn’t have the slightest idea about the game, rather than a collective strategy.

Hit concurrently by a dip in quality and an inability to sell players, both clubs are now exiled from the top four and thus unable to splash the kind of cash required to repair the messy squads bequeathed by a decade of inaction.

Speaking after Arsenal sacked Unai Emery, former Gunner Paul Merson, on Sky Sports, said Leicester boss Brendan Rodgers is the man to revitalise the Gunners.

“Leicester are the best team in the league at the moment,” he said. “But Arsenal are one of the top ten clubs in Europe. So don’t look at the next six months. Look at the all-round picture and the next five years.”

I don’t agree with him on three counts. Firstly, Rodgers is not the reason for Leicester’s success. He is a carefully selected mechanism in a vast organization that has meticulously curated a collection of highly talented young players. He coaches them, he improves them. But, without their talent and the work of those who identified it, the Northern Irishman would be largely powerless.

Secondly, as for the next five years, why would anything be different in 2025? When Wenger departed in 2018, Arsenal fans anticipated a liberating return to former glories. What they instead got under Emery was more of the same, precisely because he faced all the same structural issues as his predecessor.

Thirdly, Liverpool are clearly and by far, the best team in the league right now.

Ole Gunnar Solksjaer, meanwhile, is United’s fourth different manager since Fergie headed for the hills. Yet, in all that time they have failed to appoint a technical director of football, without which they are doomed to remain amongst the has-beens.

Even Pep Guardiola, widely regarded as the greatest manager of his generation, needs the support of Txiki Begiristain, the Man City director whose work behind the scenes at Barcelona was pivotal to the Catalans’ dominance as anything that happened on the training ground.

To assume changing managers can halt a decade of decline is to live in a bygone age. United and Arsenal are old-fashioned, hard-up and broken. To fix those issues will take a series of change in the administration and the way of business in the clubs- and the next manager won’t make a blind bit of difference.

Cover image credits: Sky Sports

.png)

Leave a Reply